I’ve been wanting to write this post for a while. Indeed, I’m inspired to every time I see a claim that “bikes give you the freedom cars can’t deliver” (or some such pontificating). While I don’t disagree with the sentiment itself (I must admit I smile to myself when biking past vehicular traffic) and certainly appreciate that this could help generate support for the cause, I can’t help but be irritated by these kinds of statements. This freedom…what does it mean? Generally speaking, academic explanations might look to Amartya Sen or Martha Nussbaum’s conceptualization of freedom as ‘the real opportunity to achieve valued ways of being and doing’ (thanks Gemini). However, looking at freedom through the capabilities approach they promote fails to grapple with the reality that one person’s pursuit of freedom might limit another’s freedom.

From a transportation perspective, it seems to me freedom means the ability to go anywhere (if you’re watching car commercials, that includes pristine ecosystems that do not have the freedom to avoid being visited by polluting vehicles), anytime, and without any barriers or bothers (and watch out if you’re the bother-er, because there is also the freedom of drivers to subject other lives to danger or denigration with likely no repercussion). What has this freedom gotten us? An individualistic society relentlessly pursuing efficiency (funny given how much time we waste zoning out on our screens…) whose zero-sum mindset is killing our planet, our neighbors, and whatever modicum of social capital we had left. Is this really the rallying cry transportation advocates want to lead with?

I recently attended my second TransportationCamp where Jarrett Walker gave the keynote. He rooted his remarks in freedom, too, by proposing right out of the gate that “urban planning should be thought of as freedom planning” (paraphrased); however, he tried to refine the notion of freedom to mean more precisely the freedom to choose how to travel from a range of options (which in turn, presumably, enables access to more destinations). Of course I support building out transit networks and walking, rolling, and biking infrastructure – we must do it, partly because it is imperative to increase access to opportunities for all ages and abilities. But Mr. Walker seemed to not consider (or not consider important) the fact that in practice, people will often still opt for driving even when viable alternatives exist, as we know from research finding how much rideshare has eroded transit ridership (or walking and riding a bike) even with high quality bus and train options. If people would rather pay more to drive – either in terms of cost or time spent in vehicular traffic – I tend to think there’s another dynamic at play.

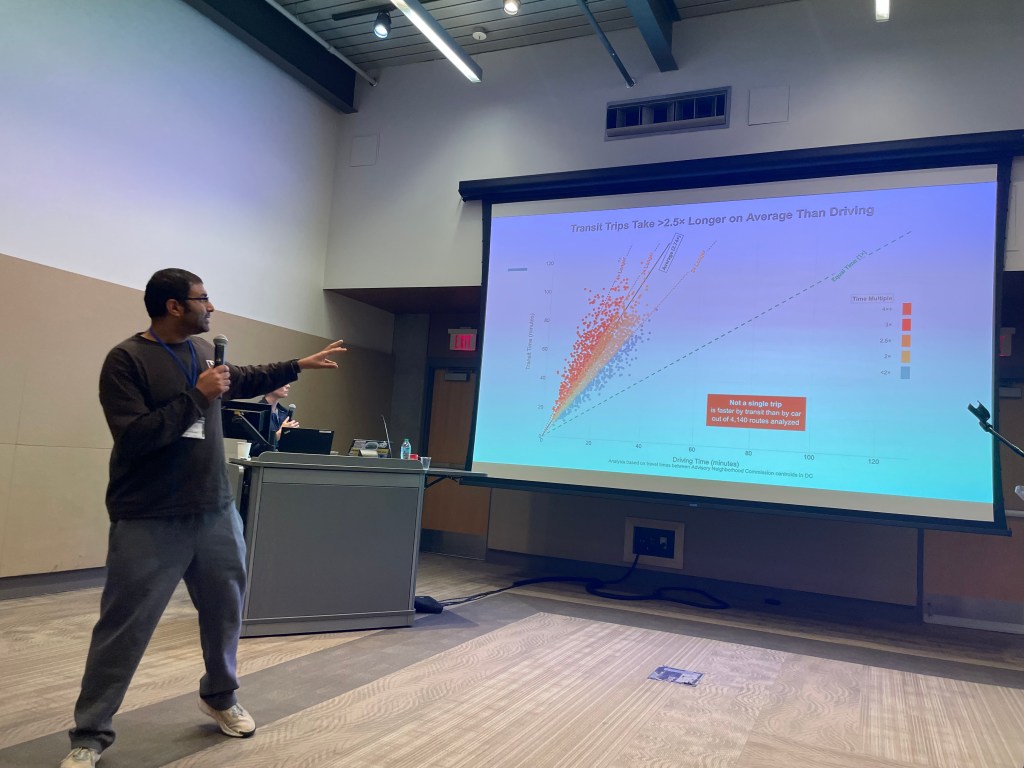

Before I explore that, though, it’s important to flag that we also know from research that there are a lot of places where public transit does not offer a compelling alternative to driving. In one session of TCamp (as it’s affectionately called), my favorite researcher Karthik Balasubramanian presented his work showing the transit travel time averaged across thousands of origin-destination pairs in DC took 2.5x longer than driving a car. I asked Jarrett about the transit time tax since it appeared to aid credible evidence to his argument about freedom and access. Surprisingly, he suggested that parity between driving and transit need not be the real goal because people would likely opt to take transit even if it was only 1.5x longer given they could do other things while in transit. While I hope Mr. Walker is right, his speech and his response to the time tax findings prompt me to think he has severely underestimated the value people (in the US, at least) derive from the cultural aspects of driving a car. Someone attempted to flesh out this tension in the Q&A and Mr. Walker’s response – that the ways the car represents freedom are only relevant when we try to nationalize the discourse on transportation policy/discuss it outside of localized (presumably urban) contexts – seems disconnected from the reality I see in the city-wide discourse I’ve studied in DC.

Why is the draw of the car so strong? My hypothesis starts from the symbolism between cars and freedom. Specifically, the freedom represented by a car allows drivers (or, riders in taxis, Ubers, Lyfts, and the like) to assert status, to flaunt speed, and to maintain separation…key ingredients for cooking up power on public streets. Thus I would posit that many people – at least those not too young, old, disabled, or poor to own or operate a car – will opt for a car, all else equal.

This gets to the heart of my gripe with hanging our transportation advocacy hats on freedom. Even when it’s ostensibly based on a freedom to choose, it still assumes the car is a neutral object. Perhaps in a showroom it is, but as soon as it comes into contact with social and environmental factors, it morphs into an influential force that has real impacts on everything outside of it. In the session I was a panelist on at TCamp, I spoke to this point during the group discussion we had after sharing different perspectives on car dominance (I think that might have been the shortest summary I’ve ever given on the conflict system of vehicular violence and the ideology of car supremacy). First, by suggesting that advocates so far seem to focus on only a few negative aspects of driving rather than articulating the dozens of harms of cars we all must contend with whether are use them or not. Second, by positing that I don’t necessarily think we need to ban cars outright but do want to eliminate the harms they cause (which, given how many they create, might result in a decline in their presence so precipitous it is essentially equivalent to a ban), beginning with a drastic reduction in the deadly speeds they are typically operated at and particularly around others not surrounded by metal. When we talk about freedom, we should be very careful to specify: freedom from what? To do what? And what do we trade off in return?

So if I don’t think freedom is the value transportation advocates should be banking on, is there a better option? Yes! But you’ll have to wait for a future post to find out. In the meantime, I invite you to get curious – what comes to mind when you envision a more peaceful transportation system? ☮️🚸

Leave a comment