A lot of people think that cities are loud. However, a more accurate framing is that cars are loud, and most cities are filled to the gills with sounds of mufflers, horns, and screeching tires (among other unpleasant noises). One of my favorite things to do when I’m visiting a city with more people-scale mobility is to stop while out on a walk and just listen…to the birds, to the people chatting away at the corner cafe, to the gentle sound of an acoustic (good word choice, trendsetters!) bike clicking by. Many of us urbanites may even recall the early days of the pandemic and how different cities sounded without the omni-present automobile. To this day, one of my most memorable rides in DC was when I had headed out on the first nice spring day in 2020 after weeks of sheltering and finding that the city streets were largely devoid of cars – despite the terrible chaos of the world at that moment, the quiet I experienced gave me a deep sense of calm (tbh could’ve also been due to not feeling threatened by four[+]-wheeled death machines at every turn 🙃).

The health impacts of car dependence go beyond the toll they take on our bodies – the effects on our mental health are just as pernicious (a different type of car brain is a separate – but no less disturbing – phenomenon). For one, all that noise can disrupt our sleep (Ding et al., 2014; Hegewald et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2012; M. G. Smith et al., 2022). This includes having trouble falling asleep, being woken up, or having otherwise disturbed sleeping patterns (thanks, drag racers on the nearby highway!). Given that data (older than me) suggests more than 18 million Americans are impacted by highway traffic noise – and that those who live in particularly car dense urban environments are subjected to especially high levels of sound – it’s a surprisingly widespread issue. What’s more, the noise can actually lead to physical health issues, too – researchers have found links between noise from cars and increased rates of cardiovascular disease. And air pollution can in turn degrade mental health (Hematian & Ranjbar, 2022)…around we go. Mood can also be impacted – annoyance caused by car noise is a real outcome measured by public health researchers. I feel so validated 🙏🏻

Others have called attention to the relationship between stress and driving, finding a positive relationship (Yang & Matthews, 2010). Shocking no one, commuting by car – especially those long hauls to work – is associated with poorer mental health due to stress (Garrido-Cumbrera et al., 2023; Beirão and Sarsfield Cabral, 2007). Thanks to disproportionate care responsibilities, we must also consider that stress associated with commuting can have more a detrimental effect on women, and that women who don’t own a car (many of whom are low-income women of color) often endure even greater stress levels as they go about their daily lives (Roberts et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2018). Beyond the findings connecting commuting and stress, the stress of just financing a car has been documented in the literature, particularly in households that have no other transportation choice and therefore must forego spending in other areas (Mattioli, 2017).

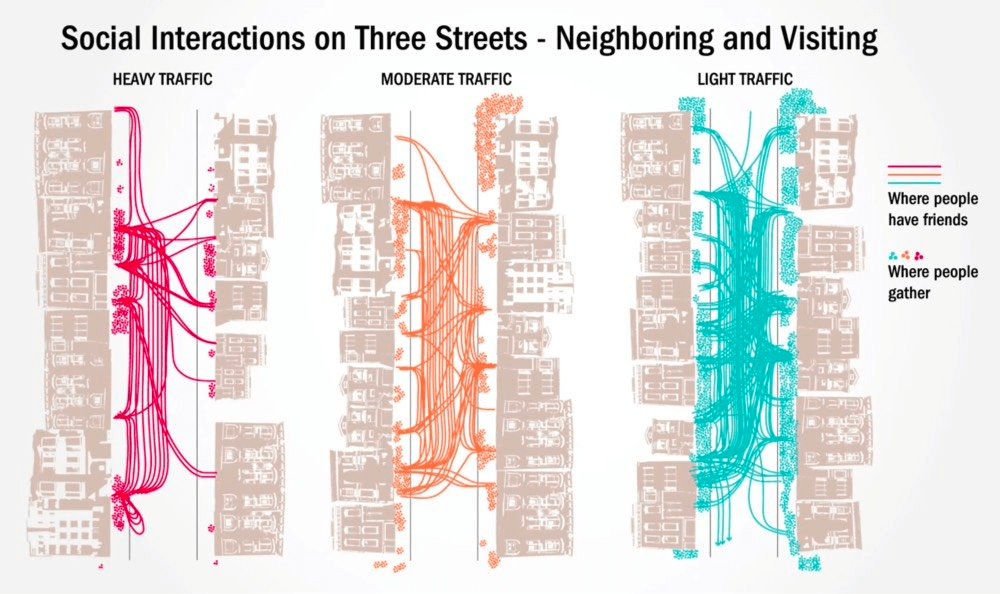

Several researchers have tied car dependence to depression, which some attribute to the sedentary nature of driving (Song et al., 2007; Sui et al., 2015). On the positive side, in one study researchers found – somehow just for men? 🤷🏼♀️ – a “protective association” between depression and walkable neighborhoods signaling that more compact communities can do wonders for our mental health (Berke et al., 2007). Indeed, there’s a complicated – and sad – story around men and worsening mental health outcomes (the ramifications of toxic masculinity roar their ugly heads yet again), but if we are to understand the full picture of the issue we must grapple with how our built environment influences our well-being. Men are not the only ones who could benefit from rethinking how our neighborhoods are designed though, especially since US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy sees our nation’s rates of loneliness as an epidemic (I’d highly recommend his book on the topic). Fortunately, we’ve known for at least 50 years that blocks with fewer cars cultivate more neighborliness and likely ward off social isolation and the degraded mental health impacts that come with it (Appleyard and Lintell, 1972). So if you want to simply maintain your relationships, opt for the small apartment closer to active and public transit networks…you don’t need all that extra space to furnish and clean, anyway.

Beyond the impacts on social cohesion, car dependence means many people are effectively excluded from participating in society. If you can’t or don’t have a car, you may be unable to access work, school, healthcare, civic institutions, or democratic processes like voting (kind of you to close all those walkable polling locations, GOP! 🙄), or at least do so without a significant time (and financial) investment (Anderson, 2018; Allen & Farber, 2020; Bierbaum et al., 2021; Landis, 2022; Lenhoff et al., 2022). In fact, nearly 25% of American adults are transportation insecure, which means they lack the means to safely and affordably get around (Murphy et al., 2022). With the many related costs of car ownership increasing (jumping 13% between 2022 and 2023, totaling an annual average of more than $12,000), many families are locked into a choice with no good options.

🧼 Soap box time! Let me be clear in case anyone is wondering: the solution to these problems is not to ensure everyone has access to a car. Every time I come across a public (or private, for that matter) report that uses car ownership as a measure of economic well-being – alongside rates of homeownership, for example – my blood boils. The fact that we equate car ownership with wealth and success reveals what is fundamentally broken with our transportation system. We need a revolutionary reframe of our metrics for what a “good life” is and to restructure our investments and policy to reflect this. Beyond it simply being a moral question, it’s also a simple logic/physics question: there is only so much space in a city, and not everyone can have a car. 🧼

“An advanced city is not one where even the poor use cars, but rather one where even the rich use public transport.”

Enrique Peñalosa

Getting back to the topic at hand, when further contemplating the mental health impacts of car dependence, we cannot ignore the tragic consequences of racial segregation on our social fabric (Candipan et al., 2021). Furthermore, we must contend with the massive intergenerational trauma borne by thousands of Black communities across the US as a result of urban highway projects destroying entire neighborhoods, an issue the federal government is attempting to address (Fullilove and Wallace, 2011; Archer, 2020; Retzlaff, 2020). That said, the fracturing of communities of color to accommodate cars continues to this day, and while it’s a start, some doubt the USDOT Reconnecting Communities grant program can truly effect change…it certainly can’t turn back time to redress the harms already experienced. This is to say nothing of the incredible anguish and destruction that the US military-industrial complex has inflicted across the globe to shore up fuel reserves for all those gas guzzlers (wars we are likely to continue to wage to power all those EVs that will resolve approximately only one of the dozens of problems cars pose).

So how can we begin to change this dynamic? Advocate for denser, more mixed-use zoning in your neighborhood. If you know an elder downsizing, find a place that resembles – dare I say it – a 15-minute city to ensure they’ll have opportunities to meet people and get activity as they run their errands. Try a week without driving to see what changes are needed to improve your active and public transit networks – and proceed to make your voice heard in government forums to push for change. Then 🚍 continue 🛴 using 🚲 those 🚶♂️other 🚃 modes. Your 🧠 will thank you!

Until next time, I invite you to get curious – what comes to mind when you envision more peaceful streets? ✌️🚸

For research articles on this topic, see:

Allen, J., & Farber, S. (2020). Planning transport for social inclusion: An accessibility-activity participation approach. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 78, 102212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.102212

Anderson, C. (2018). One person, no vote: How voter suppression is destroying our democracy. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Appleyard, D., & Lintell, M. (1972). The Environmental Quality of City Streets: The Residents’ Viewpoint. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 38(2), 84–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944367208977410

Archer, D. (2020). “White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes”: Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction. Vanderbilt Law Review, 73(5), 1259–1330.

Beirão, G., & Sarsfield Cabral, J. A. (2007). Understanding attitudes towards public transport and private car: A qualitative study. Transport Policy, 14(6), 478–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.04.009

Berke, E. M., Gottlieb, L. M., Moudon, A. V., & Larson, E. B. (2007). Protective Association Between Neighborhood Walkability and Depression in Older Men. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(4), 526–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01108.x

Bierbaum, A. H., Karner, A., & Barajas, J. M. (2021). Toward Mobility Justice: Linking Transportation and Education Equity in the Context of School Choice. Journal of the American Planning Association, 87(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1803104

Candipan, J., Phillips, N. E., Sampson, R. J., & Small, M. (2021). From residence to movement: The nature of racial segregation in everyday urban mobility. Urban Studies, 58(15), 3095–3117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020978965

Ding, D., Gebel, K., Phongsavan, P., Bauman, A. E., & Merom, D. (2014). Driving: A road to unhealthy lifestyles and poor health outcomes. PloS One, 9(6), e94602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094602

Fullilove, M. T., & Wallace, R. (2011). Serial Forced Displacement in American Cities, 1916–2010. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 88(3), 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9585-2

Garrido-Cumbrera, M., Braçe, O., Gálvez-Ruiz, D., López-Lara, E., & Correa-Fernández, J. (2023). Can the mode, time, and expense of commuting to work affect our mental health? Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 21, 100850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2023.100850

Hegewald, J., Schubert, M., Lochmann, M., & Seidler, A. (2021). The Burden of Disease Due to Road Traffic Noise in Hesse, Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), Article 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179337

Hematian, H., & Ranjbar, E. (2022). Evaluating urban public spaces from mental health point of view: Comparing pedestrian and car-dominated streets. Journal of Transport & Health, 27, 101532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2022.101532

Kim, M., Chang, S. I., Seong, J. C., Holt, J. B., Park, T. H., Ko, J. H., & Croft, J. B. (2012). Road Traffic Noise: Annoyance, Sleep Disturbance, and Public Health Implications. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(4), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.014

Landis, J. D. (2022). Minority travel disparities and residential segregation: Evidence from the 2017 national household travel survey. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 112, 103455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2022.103455

Lee, J., Vojnovic, I., & Grady, S. C. (2018). The ‘transportation disadvantaged’: Urban form, gender and automobile versus non-automobile travel in the Detroit region. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 55(11), 2470–2498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017730521

Lenhoff, S. W., Singer, J., Stokes, K., Mahowald, J. B., & Khawaja, S. (2022). Beyond the Bus: Reconceptualizing School Transportation for Mobility Justice. Harvard Educational Review, 92(3), 336–360. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-92.3.336

Mattioli, G. (2017). ‘Forced Car Ownership’ in the UK and Germany: Socio-Spatial Patterns and Potential Economic Stress Impacts. Social Inclusion, 5(4), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i4.1081

Murphy, A. K., McDonald-Lopez, K., Pilkauskas, N., & Gould-Werth, A. (2022). Transportation Insecurity in the United States: A Descriptive Portrait. Socius, 8, 23780231221121060. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231221121060

Retzlaff, R. (2020). Connecting Public School Segregation with Urban Renewal and Interstate Highway Planning: The Case of Birmingham, Alabama. Journal of Planning History, 19(4), 256–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513220906386

Roberts, J., Hodgson, R., & Dolan, P. (2011). “It’s driving her mad”: Gender differences in the effects of commuting on psychological health. Journal of Health Economics, 30(5), 1064–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.07.006

Smith, M. G., Cordoza, M., & Basner, M. (2022). Environmental Noise and Effects on Sleep: An Update to the WHO Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives, 130(7), 076001. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP10197

Song, Y., Gee, G. C., Fan, Y., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2007). Do physical neighborhood characteristics matter in predicting traffic stress and health outcomes? Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 10(2), 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2006.09.001

Sui, X., Brown, W. J., Lavie, C. J., West, D. S., Pate, R. R., Payne, J. P. W., & Blair, S. N. (2015). Associations Between Television Watching and Car Riding Behaviors and Development of Depressive Symptoms: A Prospective Study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(2), 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.006

Yang, T.-C., & Matthews, S. A. (2010). The role of social and built environments in predicting self-rated stress: A multilevel analysis in Philadelphia. Health & Place, 16(5), 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.005

Leave a comment