The way we build our cities and communities says a lot about what we value. When you walk around your neighborhood, what design and planning decisions do you see and what do they tell you about what our society prioritizes? Whose movements and activities do they most facilitate? Whose needs do they most ignore? What are the ways in which our built environment attempts to reject the notion that as humans, we are inherently vulnerable and thus reliant on systems of interdependence?

What does the urban peacebuilding literature have to say about these questions? As several authors detail (Zeiderman, 2020; Bachmann & Schouten, 2018), massive concrete infrastructure projects have been used to shape peacebuilding processes in conflict-torn societies across the world (though notably, none of the examples used focus on how infrastructure in western countries foments conflict). For example, Bachmann & Schouten explore how a simple culvert in eastern Congo is part of a much broader network of infrastructure projects “based on the logic that re-establishing road movement along key transport links and creating corridors of security is of critical importance to reinforcing state presence in the Eastern provinces as is [sic] a top priority for the Government of DRC and the UN mission” (p. 382). In another example, Zeiderman (2020) notes how a bridge that was constructed in one Colombian port city challenged the dominance of criminal organizations that had taken advantage of the port’s location and infrastructure to carry out illegal activity, but also had the unintended consequence of drying up the legal activities and jobs associated with the port’s operation, leaving many locals without the work they once depended on.

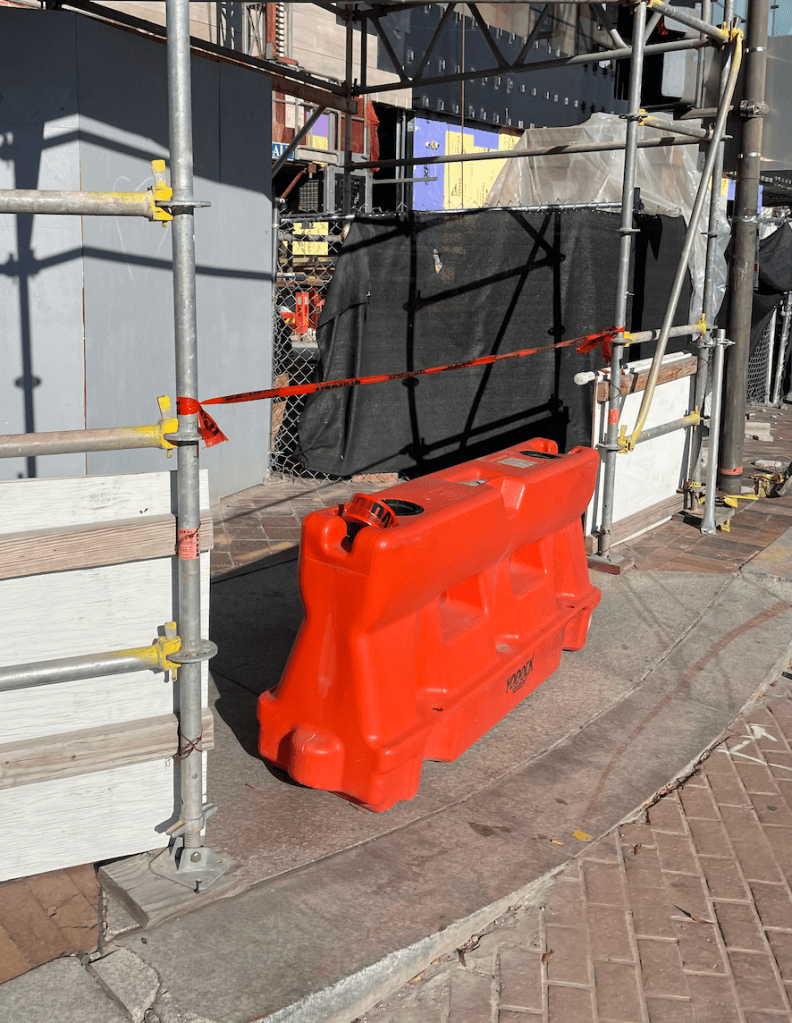

However, when considering their investigations of infrastructure, one is implicitly asked to make a key assumption about the types of infrastructure being discussed (one need look no further than their article titles, both of which feature a play on the word “concrete”). The infrastructure paradigms they are critiquing are focused on the big, grey sort that creates bridges and builds water treatment plants. While these no doubt provide helpful services, someone familiar with the US context may experience a feeling of déjà vu given that policy debates that proliferated around Biden’s infrastructure legislation about what constitutes “infrastructure.” In fact, liberals were keen to include so-called “care” infrastructure (which conservatives might have depicted as “soft” infrastructure) that focused on the types of systems and services that are mainly left to women (and even more frequently low-income women and women of color) such as education, health care, and dependent-care. Despite estimates that unpaid care-work in the US represented 20% of the country’s gross domestic product (totaling more than $3 trillion), it is not seen by many as valuable enough to warrant support through infrastructure packages (Vereinte Nationen, 2015).

Therefore, it is notable that the same type of infrastructure that is seen as a legitimate use of state money is also what is being exported to countries around the world where western powers exert disproportionate influence over peacebuilding efforts. While we can certainly take issue with global powers choosing what types of projects receive their financial backing, what if instead those countries spent their billions of dollars on the care economy? I’d like to see the peace dividends that would be realized with paying teachers more and investing in schools, paying medical staff more and improving hospitals, and compensating women for the unpaid work they do to care for children, elders, and their larger community.

I’d also like to see what that would look like in the US. We needn’t even focus on such soft infrastructure as child care to see the benefits of taking a woman-centered approach to infrastructure investment. For example, people who identify as women (particularly in urban areas) are more likely to take shorter trips for a variety of reasons and are more likely to take those trips by public transit, walking, or biking (de Madariaga, 2013). For one, historically, their male spouses (recognizing that the literature has to a great extent focused on heterosexual marriages) tended to take longer trips for one purpose (commuting to work), which required the use of a vehicle (which, in the case of single-vehicle households, further constrained the mobility of women); while a larger proportion of women are in the workforce today than their foremothers, there is still a discrepancy between their labor participation and that of their male counterparts. Indeed, many women continue to work part-time, work remotely, or have alternate work situations so that they can shoulder care duties (which are disproportionately managed by women) which prompt different travel patterns.

In this case, even if we were to take a traditional view of infrastructure projects as those built of steel and concrete, we could still envision a transportation network that catered to the needs of women who are significantly more likely to shoulder care responsibilities by investing in public transit, pedestrian safety improvements, and protected bike lanes. Several municipalities in Sweden took an interesting approach to this by evaluating their snow plowing practices – by shifting their priorities from regional highways to neighborhood sidewalks and bike lanes, crashes (and associated health-care spending) went down by 50%. That is because women – who are more likely to use local active transportation infrastructure – didn’t have to make as many hospital visits for injuries (which had tended to be more serious ones) caused by slippery sidewalks – which they had been doing at disproportionately higher rates than their male counterparts prior to the policy change (Criado-Perez, 2019).

By reframing how we think of infrastructure – especially transportation infrastructure that supports care work – we realize economic, health, and education opportunities – we can change the predominant culture from one based on the dominance of cars to one based on the needs of people, from one driven by the desire for efficiency to one guided by the criticality of care.

Leave a comment