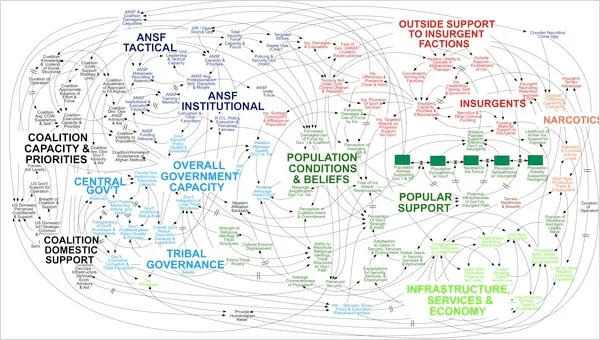

In my Peace Engineering and Participatory Approaches to Narrative Methodology class this week, we talked about that infamous PowerPoint slide trying to detail all the aspects of the American strategy in Afghanistan and whether it was helpful to have that view of a conflict system, particularly from a complexity theory perspective. The consensus seemed to be: “Nope, not helpful.”

On the one hand, I understand that it’s not a productive way to go about understanding a problem – how can you possibly figure out how to enact change when something is as complicated as a country half a world away that most people can’t find on a map? Heck, how can you enact change when something is as complicated as a single relationship between two people? On the other hand, I think it our responsibility as scholar-practitioners in the peace and conflict resolution field to really seek out the nuance, search out the complexity, and appreciate the dynamism of the systems we’re hoping to change.

If you tried to implement a solution without understanding the broader issues or intersecting challenges, your solution may end up exacerbating another node in the web of the conflict. I think our principal task as peace practitioner-scholars is instead to be able to see the big picture (rather than ignore it), and figure out (and/or work with others to identify) where our efforts can have the biggest positive impact given the web of relationships that exist. After all, I think that is why we have a hot mess of federal regulation about all sorts of policy issues – without fully comprehending how things are interconnected, you quickly get a “Christmas tree ornament” approach where instead of addressing the root cause of something, you just tack on another new thing that becomes a band-aid solution at best and a solution with myriad unintended consequences at worst. It’s definitely not easy, but I worry about the defeatist approach expressed by some in class that essentially said, “this view is pointless.”

It seems to me a more generative dialogue would be along the lines of, “to what extent can we understand what’s going on here and where does it make sense to focus our efforts, knowing that we can’t handle it all, there are things we don’t know we don’t know, and we can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” What I think is powerful about this approach is that it also opens space for people to be agents of change in a way that is most meaningful – and accessible – to them. In fact, it’s NOT about understanding every facet of the broader system, but recognizing that there *is* a system, and being a bit more thoughtful and intentional about solutions. At that point in the process is when I think “adaptive peacebuilding” (to use Cedric de Coning‘s language…it seemed similar to “tactical urbanism” in my world) becomes really exciting because you’re making a small change to the system to test your assumptions about how it will impact the broader system (and if the impacts are not what you anticipate and lead to worse outcomes, you haven’t sunk a bunch of resources into it and locked future generations into a permanent bad change).

This idea reminded me of a reading I did for my qualitative research methodology class this week on indigenous paradigm research. In it, the author highlighted what the Native American epistemological paradigm would be: “Everything is connected in some way to everything else. It is therefore possible to understand something only if we can understand how it is connected to everything else.” (Bopp et al., 1989, p. 26 – as quoted in Polly Walker’s chapter in D. Bretherton, S. F. Law (eds.), Methodologies in Peace Psychology, Peace Psychology Book Series 26, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-18395-4_8). As we work to decolonize research, how might we better account for the messy interconnectedness of the world as we seek change?

Leave a comment